The History of Kosovorotka

Kosovorotka has traditionally been considered as a symbol of folk attire among Russian men. According to historical evidence, the first written records of the Kosovorotka date from the middle of the XII century and are associated with the city of Suzdal – the center of Russian statehood in North-Eastern Russia. This period of our history is connected with the name of the Holy Blessed Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky (1111 – 1174), the ruler of Vladimir-Suzdal Russia, the first Russian Autocrat, during which the political and economic center of Ancient Russia moved from the South-West to the North-East. “The First Great Russian”, it’s how V.O. Klyuchevsky, the famous Russian historian, called Grand Duke.

It is not surprising that it was during the reign of Andrei Bogolyubsky in the lands that subsequently formed the skeleton of Great Russia that Kosovorotka began its victorious march so that in modern times (XVII-XIX centuries) it would become an exclusively Russian folk shirt.

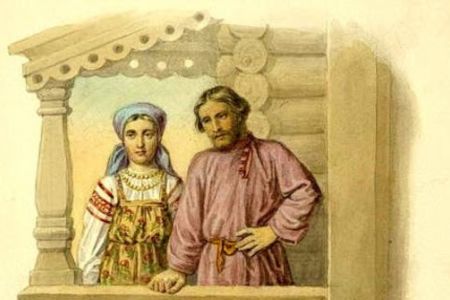

Kosovorotka firmly entered the national memory and historical traditions of the Russian people. At the same time, it had an omnipotent character: the kingshirt was worn by the kings (Ivan the Grozny, the Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich), and emperors (Alexander III, Nikolai II), and high-born boyars, and merchants, and philistinism. But truly unlimited was the devotion to the turn of the Russian peasantry – the basic basis of the Russian State

Kosovorotka got its name because of the features of the collar: the cut on the shirt was not in front, as is customary in modern shirts, but on the side, usually on the left. Interestingly, Kosovorotka could have a collar and not have it.

There are several hypotheses why the Russians shifted the classic straight cut to the left side:

1. the assumption of Academician Dmitry Likhachev, which boiled down to the fact that the oblique collar allowed to reliably hide the chain and the pectoral cross: it did not fall out of the shirt.

2. Dmitry Zelenin, the famous Russian ethnographer, believed that such a complex cut made it possible to protect a person from the cold and wind, because it was more difficult to blow out the icy air in a shirt.

3. A number of researchers are of the opinion that the oblique gate is still a tribute to the military tradition. It was on the left side that chain mail was fastened, since it was easier to protect the neck from impact (the left side of the body was covered with a shield). If the smell was on the other side, then when you hit with a saber or a sword, it was easy to get into the cut – and then that’s it, head from shoulders! By the way, for the same reason, cotton armor later began to be fastened – on the left side, like a braid.

Men’ Kosovorotka

Of course, traditionally the word “Kosovorotka” is used in relation to the men’s shirt. Traditionally, they sewed it from hemp cloth, but then several more basic materials were added:

• cotton fabric;

• linen cloth;

• silk – for ceremonial, festive shirts or lower shirts of noble men.

The shirt was worn constantly; common people – like outerwear, to know – like underwear. The braid was necessarily worn out and girded with a sash, which was sometimes decorated with tassels (for holiday dresses).

Shirts could have different purposes and were worn on certain occasions:

-

mowing – a festive shirt that men and women wore on the first day of mowing, that is, the harvest;

-

a wedding shirt – usually, it was worn as a holiday and was often inherited, carefully stored;

-

everyday shirt etc.

Fabrics for braids could be unpainted (for everyday shirts) or dyed by craftsmen. The most elegant was considered the red braid, which was often worn by grooms. For the holidays, too, they tried to put on a red shirt.

Kosovorotki necessarily beautifully decorated with embroidery, which had a protective value. It was believed that certain characters would help ward off trouble from the owner of the shirt. For example, rhombs were almost always embroidered – a symbol of the sun in Russia. Often, periwinkles were embroidered on men’s shirts – this is a symbol of life that will never fade. Often, grapes were used as an ornament – a symbol of fertility.

Today, not only the participants in creative singing and dancing groups continue to wear a kosovorotka. The followers of ancient piety – the Old Believers both in Russia and abroad, still wear a caftan and a braid for worship, emphasizing the authenticity of the Russian costume.

Women’ Kosovorotka

Women’s braids are most often called simply shirts or shirts. It was the basis of a women’s costume. Shirts were floor-length; at home it was allowed to walk in a single braid, unless, of course, there were guests in the hut. Noble women wore “maids” home-made shirts of delicate silk.

A sarafan (in northern culture) or poneva (in the south of Russia) was worn over a shirt. The shirts of the married and unmarried girls were different. In general, shirts were sewn for a variety of cases:

-

everyday shirt – it was up to the floor and had a simple straight cut; she was usually called the camp;

-

reaping shirt – the laity wore it on the first day of the harvest; the outfit was considered festive;

-

funeral – mourning shirts;

-

wedding – the happiest and most beautiful shirts, which were carefully stored and often inherited;

-

shirts for witchcraft and other mystical rites – such clothing was called a sleeve and had very long sleeves with slots, thanks to which they could be tied or fastened with bracers; it was impossible to work in such clothes, and therefore the expression “work through the sleeves” arose;

-

killer – a very interesting type of shirt for brides; the last week before the wedding, the girl wore such an outfit and was “killed” by her maiden life, which she would leave after she got married.

Interesting! Almost all female braids were decorated with embroidery, and even with the adoption of Christianity, traditional pagan symbols were embroidered – plant patterns, rhombuses, images of horses, pagan deities and their symbols. The only type of shirt for women that was not decorated with anything is the widow’s shirt. Even the mourning funeral dresses were beautifully embroidered with thread.

Baby’s Kosovorotka

Children’s Коsovorotkas were no different from adult Kosovorotkas, except for size. Moreover, there were several interesting traditions when sewing them:

-

The child’s clothes were always just a shirt, and nothing more.

-

The first diaper for a newborn baby, that is, his first clothes, was the worn braid of his father (for a boy) or mother (for a girl). It was believed that this protects the child from the evil eye and damage. For the same reason, absolutely all children’s shirts were beautifully embroidered – there were protective symbols on the fabric, for example, an ornamental image of the goddess Beregini.

-

The cut of the shirts for girls and boys did not differ until they reached the age of the bride or groom, then the clothes became the same as

-

After the “initiation rite” (that is, after the adolescent was recognized as the bridegroom or bride), the girls and boys received other clothes. Girls – ponevu skirt, boys – ports.

Children’s braids were called shirts. It was believed that this word came from the word “rub”, which meant “piece of fabric.” From the same word came the word “shirt” or “shirt” known to us today.

The child received a kosovorotka of new tissue (new items) only after he turned 3 years old. Up to this age, it was believed that the child was too weak, and only the powerful strength of the father or mother, enclosed in the fabric from their kosovorotkas, allows the baby to be protected from evil forces, from diseases.